Self and Other in the Islamic Cultural Paradigm Featured

The "model" plays a central role in defining "role models and ideals," serving as a compass that guides human orientations across various life domains. In the family, it is the "father figure"; in the nation, the "hero"; in history, "triumph models"; in international and regional relations, "national identity"; and in beliefs and ideologies, the "religion model." These models captivate individuals, steering them toward specific paths and choices at crossroads.

When a "model" is chosen, it signals the individual's alignment and distinguishes them from the "other," whom they have consciously chosen not to emulate in that area of choice.

The cultural domain is not merely one among many arenas for selecting a model; the "cultural model" becomes a criterion shaping preferences across numerous fields once chosen, embraced, and loyally adhered to. The culture that forms a person's identity directs their choices in role models, ideals, and values, encouraging allegiance to some and opposition to others, and motivating dedication to specific goals while forsaking alternatives. The "cultural model" also defines the future model that individuals aspire to create within their social realities.

Self and the Other in Cultural Context

While all humanity originates from a single soul, Divine wisdom ensured diverse paths for humanity, including multiple languages, colors, methodologies, and laws, as means of competing to inhabit Earth, achieve benefits, and procure material and intangible resources. As such, humanity divides into nations, tribes, and cultures.

The "self" is recognized by distinguishing features and constants, not by shared attributes with the "other." Given the modern Arab-Islamic reality, marked by cultural and civilizational encounters specifically with the Western model, discussion about "self" and "other" culturally must clarify the distinctive features of the Islamic cultural model compared to the Western one. This does not imply ignoring areas of shared human knowledge where truths, laws, and fruits of sciences transcend cultural identities, fostering collaboration among humanity's diverse cultural entities.

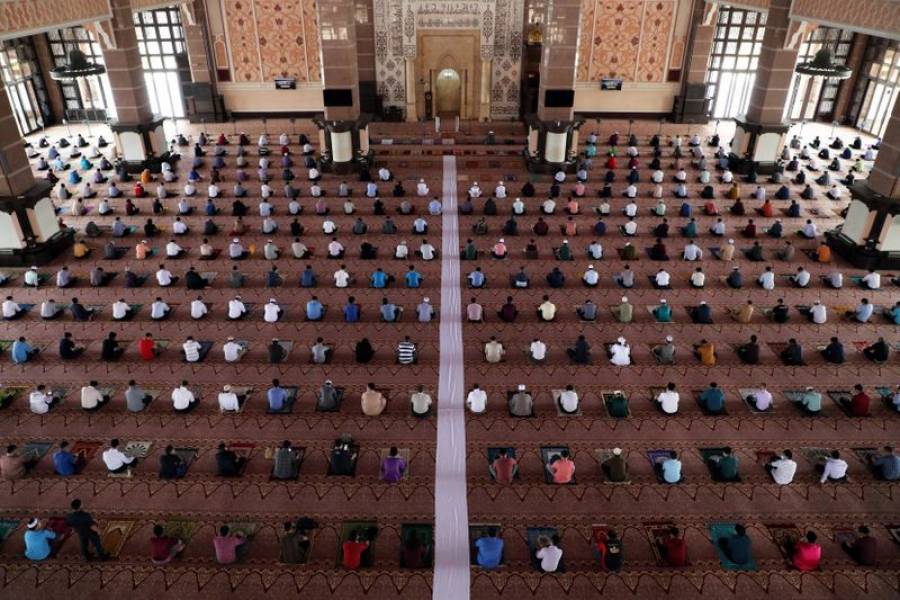

Islam as a Component of Our Cultural Identity

Islam constitutes our cultural identity and shapes our cultural model, distinguishing it from the Western "other" only where divergence exists. This creates a relationship characterized by "distinctiveness and interaction," balancing two extremes: excessive isolation, which views the relationship as one of "separation and conflict," and excessive mimicry, which sees it as "similarity and imitation." Just as fingerprints differentiate individuals, the cultural identity of a nation is distinguished by its models that combine divergence and defining traits, without denying shared truths in human experiences, sciences, and arts.

Selective Cultural Engagement

Throughout history, Muslims selectively interacted with various civilizations. They adopted astronomy and mathematics from India while rejecting philosophical and cultural ideologies. Similarly, administrative systems were taken from Persia, avoiding religious beliefs. From Byzantine Romans, adopted record-keeping methods but not legal systems. In engaging with Greek heritage, Muslims embraced experimental sciences while discarding theological and literary works saturated with mythological paganism.

The same principle applied during Europe's Renaissance interaction with Islamic heritage. Europeans utilized Muslim advancements in experimental sciences and methodologies while reviving Greco-Roman models rather than emulating the Islamic cultural framework.

Ibn Rushd as a Model

The European Renaissance's engagement with Ibn Rushd (Averroes) exemplifies selective interaction between cultural models. Europe accepted "Ibn Rushd: the commentator on Aristotle," aligning with their philosophical trajectory, but rejected "Ibn Rushd: the harmonizer of human wisdom and Islamic law." His Islamic cultural model, grounded in faith-driven rationality, contrasted sharply with Europe’s secular, enlightenment-driven ideology.

Lessons from the Early Egyptian Renaissance

During Egypt's early modern experience under Mohamed Ali Pasha, cultural interaction exemplified healthy engagement with the "other." Rifa’a Rafi’ Al-Tahtawi advocated for benefiting from European scientific knowledge, especially practical sciences tied to progress, emphasizing that these disciplines originated from Islamic heritage. Simultaneously, Al-Tahtawi encouraged revitalizing the Islamic cultural model by promoting Sharia and Islamic traditions, highlighting its distinction from European ideologies.

Colonial Impact on Cultural Models

However, colonial domination reversed this dynamic, depriving Arabs of essential scientific advancements while inundating them with Western cultural elements alien to their own heritage.

References:

(1) “The Complete Works of Rifa’a Al-Tahtawi,” Vol. 1, pp. 335, 435, 441, 511, and Vol. 2, pp. 951, 97; Study and Verification by Dr. Mohammed Amara; Beirut Edition, 1973. (2) Omar Touson, “Scientific Missions During the Era of Mohamed Ali, Abbas, and Said,” pp. 23, 24, 219, 11, 162, 163; Cairo Edition, 1934.