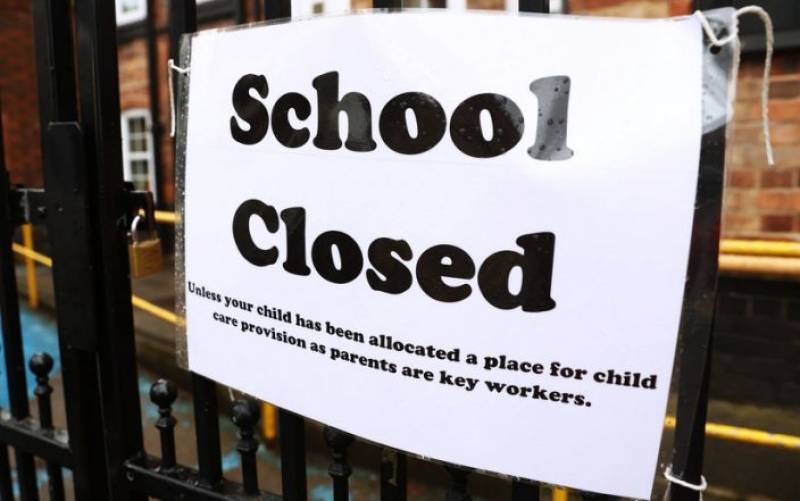

Teaching unions on Friday night demanded the closure of every school in the country after Gavin Williamson caved in to pressure to shut all primaries in London.

The Education Secretary was forced into a U-turn after councils threatened legal action over his decision to keep some schools in the capital open.

The move raises the prospect that pupils in other areas could also be kept at home, as a leading union insisted that "what is right for London is right for the rest of the country".

Dr Mary Bousted, the joint general secretary of the National Education Union, said the Government had corrected "an obviously nonsensical position", adding that ministers must "do their duty" by closing all primary and secondary schools to contain the virus.

It left the Government's policy on school reopenings in chaos just two days after Mr Williamson had resisted pressure from Cabinet colleagues to close schools on a region-by-region basis.

The development comes after Government scientific advisers warned that the spread of the new strain of coronavirus was unlikely to be halted if schools reopened, while an Imperial College study published on Friday said it may not be possible to "control transmission" if children go back to classes as planned.

There were fresh warnings on Friday night that the closure of schools to all but vulnerable children and the children of key workers will prove disastrous for students' education, with new questions about whether exams will go ahead as planned later in the year.

The Government has attempted to resist calls to close schools in recent weeks after the impact of doing so during the first lockdown was revealed. Analysis by the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) charity revealed the decision had wiped out close to 10 years of progress in narrowing the attainment gap in England.

Meanwhile, scientists are divided on the impact of closing schools. Professor Tim Spector, the lead scientist on the ZOE Covid Symptom Study app, said children had been affected "the least of all age groups" despite rising cases, adding: "So if you want actions based on science,closing schools is a bad idea."

Labour council leaders in London gloated after forcing Mr Williamson into his latest U-turn. Danny Thorpe, the leader of Greenwich Council, said he was "absolutely delighted" that the Education Secretary had "finally climbed down".

Mr Williamson said the list of local authorities required to keep schools closed was being kept "under review", suggesting pupils' return could be further delayed.

The Government's current policy is to keep primary schools closed in some Tier 4 areas in the South-East, while secondary school pupils in years 11 and 13 will return on January 11 and others on January 18.

Several London districts with high coronavirus rates had been missed off the Government’s list of 50 "Covid hotspots" where primary schools were forced to close to most pupils for the next two weeks.

Eight council leaders in London had signalled that they could mount a legal challenge in response to Mr Williamson's original plan, calling the proposal "unlawful on a number of grounds".

The Education Secretary said expanding school closures had been a "last resort and a temporary solution", with primary schools in the capital now being encouraged to teach most of their pupils online.

But Dr Bousted said: "The question has to be asked: why are education ministers so inadequate and inept? Who is advising them?

"And what is right for London is right for the rest of the country. With the highest level of Covid-19 infection and hospitals buckling under the tsunami of very ill patients, it is time for ministers to do their duty – to protect the NHS by following Sage advice and close all primary and secondary schools to reduce the 'R' rate below one."

Research from Imperial College into the new "mutant" Covid-19 variant found it was directly affecting a greater proportion of those aged under 20. Axel Gandy, the chairman in statistics at Imperial College, said infections of the new variant would probably have tripled in two to three weeks under November's lockdown conditions.

"Overall, we've been able to determine that the new variant increases the reproduction number, so that's the number of people infected on average per infected person in the future, by about 0.4 to 0.7," he said. "That doesn’t sound like much, but the difference is quite extreme."

The Department for Education has said it will review the decision on school closures in the hotspot areas by January 18, but Boris Johnson has suggested this could be pushed back if coronavirus cases surge.

The decision to shut primary schools across London is the latest in a series of U-turns from Mr Williamson, including on exam results and face coverings in schools. It came after the eight London council leaders wrote to him to say they were "struggling to understand the rationale" behind a move that ignored "the interconnectedness of our city".

They said they had received legal advice that omitting some authorities from the list of areas told to take teaching online "is unlawful on a number of grounds and can be challenged in court".

The leaders of the Labour-run boroughs of Islington, Camden, Hackney, Lambeth, Lewisham, Greenwich, Haringey and Harrow all signed the letter, and Mr Thorpe said: "This is a decision that vindicates our safety-first approach we took at the end of the last term in the best interests of Greenwich. Faced with an exponential growth in Covid cases, we were clear immediate action was required.

"There remain huge questions to answer about how they ever came to this decision in the first place, and we will continue to push for those answers."

Kate Green, Labour's shadow education secretary, said: "This is yet another Government U-turn, creating chaos for parents just two days before the start of term. Gavin Williamson's incompetent handling of the return of schools and colleges is creating huge stress for parents, pupils, and school and college staff and damaging children’s education."

Ms Green called on Mr Williamson to "clarify" his position on schools in Tier 4 and set out the criteria for reopening.

It comes amid suggestions that the Government is considering making masks compulsory in secondary school classrooms. Schools Week reported that Department for Education officials had told a briefing on Wednesday evening that it would act to ensure teachers and pupils in Year Seven and above wear face coverings in class settings.

Sage advised ministers to extend the use of masks to "settings where they are not currently mandated, such as education, workplaces, and crowded outdoor spaces". The advisers also recommended "specifying higher performance face coverings and masks".

The Telegraph

FIFA on Thursday canceled men’s U-20 and U-17 World Cup tournaments in 2021 for the novel coronavirus.

"As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bureau of the FIFA Council has decided to cancel the 2021 editions of the men’s FIFA U-20 World Cup and FIFA U-17 World Cup, and to appoint Indonesia and Peru respectively, who were due to host the tournaments in 2021, as the hosts of the 2023 editions," the world football's governing body said in a statement.

So Peru will host the FIFA U-17 World Cup in 2023.

In the same year, the FIFA U-20 World Cup will be held by Indonesia./aa

President-elect Joe Biden is weighing a multibillion-dollar plan for fully reopening schools that would hinge on testing all students, teachers and staff for Covid-19 at least once a week, according to four people with knowledge of the discussions.

The proposal under consideration calls for the federal government to cover the cost of providing tests to K-12 schools throughout the country. These could then be administered regularly by staff at each school, providing results in minutes.

The developing plan closely tracks with recent recommendations from The Rockefeller Foundation to invest billions into the creation of a K-12 testing system that would reassure teachers and students it is safe to resume in-person schooling. Biden has vowed to reopen the majority of schools within his first 100 days in office, amid growing concerns about the educational and mental health toll that months of remote learning has taken on a generation of students.

But such a strategy would require a sharp increase in the manufacturing of rapid tests and new lab capacity being brought online over the next several months, as well as incentives to convince states and local school districts to adopt the more intensive testing regime.

Biden transition officials are still trying to determine the exact price for regular testing in the nation's schools. One person close to the deliberations pegged the cost at between $8 billion and $10 billion over an initial three-month period.

That would likely need to be funded through a new coronavirus aid package that Biden has pledged to pursue as soon as he takes office next year.

"It's certainly the presumption of the Biden effort that there will be an opportunity for him to pass an economic stimulus Covid relief bill in the first 100 days, and in that bill should be money for schools," the person close to the deliberations said.

Biden’s transition team has not responded to multiple requests for comment.

The emerging school testing plan represents a core element of the incoming president's effort to bring the pandemic under control and get most students back in the classroom as soon as possible.

Biden said earlier this month that reopening most schools is one of his top three pandemic-related priorities. And his choice for education secretary, Miguel Cardona, spent recent months pressing for the continuation of in-person learning as Connecticut's education commissioner.

Transition officials have spent weeks developing the reopening proposal, which will likely also recommend investments in upgrading schools' air filtration systems and other infrastructure that could help guard against the virus' spread.

Several diagnostics manufacturers and labs are in ongoing discussions with the Biden team about how to source tests and implement the screening plan, according to multiple people familiar with the discussions.

The transition team has also had conversations with the Rockefeller Foundation about school screening. “The Rockefeller Foundation and the Biden team are in lockstep on how to do K-12 testing,” a diagnostics industry source said.

Rockefeller Foundation spokesperson Ashley Chang declined to comment on the group’s interactions with the Biden team. “Our plan to safely reopen — and keep open — America's schools speaks for itself,” Chang said. “This can be achieved by mounting an extraordinary scale up of testing in K-12 schools, where teachers and staff are tested twice a week and students once a week through the end of the school year.”

The organization released a white paper last week that proposed testing all students once a week and teachers twice a week, at an estimated cost of $42.5 billion for the remainder of the current school year — far higher than the price tag for Biden’s nascent plan. Rockefeller suggested starting the screening program in elementary schools in early February, followed by middle schools by mid-February and in high schools by March.

The Biden team is discussing testing students, teachers and staff only once a week, and saving money and time by relying on rapid tests rather than lab-based PCR testing, according to a person familiar with the discussions. Another way to cut down on the cost of the program would be to pool samples from multiple students and test them using PCR at regional testing labs across the country that could be opened, according to the Rockefeller plan.

That strategy represents a break from the Trump administration's approach toward efforts to reopen schools. The federal government bought more than 150 million Abbott rapid tests in recent months with the goal of helping states boost testing in schools, but let states decide how to use most of that supply. Many governors chose to use the tests more broadly, limiting the help for schools, and millions of the rapid tests have not been used yet.

Trump testing czar Brett Giroir last week acknowledged that universities’ repeated testing of students and staff during the past months helped limit infections. But the HHS official pointed to recent CDC research that suggests mitigation measures like installing plexiglass shields, wearing masks, using hand sanitizer and cleaning supplies can help minimize the risk of Covid-19 spread for younger students.

“Any suggestion that the nation requires hundreds of millions or perhaps billions of more tests in order to open schools is contrary to the evidence and dangerous to our children,” Giroir told reporters.

Susan Van Meter, executive director of diagnostics lobby AdvaMedDx, said that while school-aged children appear less likely than adults to spread the virus, the risk is not zero.

“Individual member companies — and we represent all of them — are appreciating dialogue with the transition about the continual effort to ramp up testing and extend reach of testing, including for K-12 schools,” Van Meter said.

Health technology diagnostics company Color, which has worked with California officials and diagnostics manufacturer PerkinElmer to coordinate Covid-19 testing for the state’s recently opened laboratory, released a white paper and transmission model this month examining how testing could help K-12 schools reopen.

“Proactive testing of teachers and staff once or twice a week can help catch introductions early, before they spread widely through the school,” the Color paper states. “Especially in secondary schools, once- or twice-weekly testing amongst students should also be considered to further reduce the likelihood of a large outbreak amongst the full population.”

The Biden team has yet to finalize the testing plan, and several key elements that could determine its scope remain in flux. Officials haven’t determined how to incorporate private schools into the proposal, or what incentives are needed to get states and localities to follow the recommendations.

Also unresolved is whether the federal government would cover the cost of school testing programs that are already in place. And while Biden advisers and The Rockefeller Foundation have both argued that the federal government should use the Defense Production Act to increase the country’s testing capacity, it’s not clear how quickly that would increase the supply of rapid tests.

Color CEO Othman Laraki told POLITICO putting in place a K-12 screening system could be difficult, given the need to navigate the relevant science, the logistics of rolling out tests to students and teachers and the politics of building community support from parents and teachers’ unions. “The big part of this is kinda solving those three problems at the same time,” Laraki said.

Just creating enough testing capacity will be challenging, said Julie Khani, the president of the American Clinical Laboratory Association. The lab lobby, whose membership includes LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics, believes “significant investment” into new machines, testing supplies, lab staff, reporting systems and transportation logistics would be necessary.

“We remain focused on working with policymakers to ensure labs can make these investments and increase capacity for the innovative diagnostics our country needs, now and in the future,” Khani said.

Biden’s team has kept a close eye on the plan's price tag, amid worries that Republicans will resist the president-elect’s calls for passing another massive stimulus package early next year.

Officials in particular have discussed testing students, teachers and staff more frequently than once a week, but are wary that could send the plan’s cost ballooning.

"We had debates about how much you should test, should it be twice a week," said a person close to the deliberations. "But that doubles the price."

Politico

WASHINGTON – More than 70 cadets at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point were accused of cheating on a math exam, the worst academic scandal since the 1970s at the Army's premier training ground for officers.

Fifty-eight cadets admitted cheating on the exam, which was administered remotely because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of them have been enrolled in a rehabilitation program and will be on probation for the remainder of their time at the academy. Others resigned, and some face hearings that could result in their expulsion.

The scandal strikes at the heart of the academy's reputation for rectitude, espoused by its own moral code, which is literally etched in stone:

“A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal, or tolerate those who do.”

Tim Bakken, a law professor at West Point, called the scandal a national security issue. West Point cadets become senior leaders the nation depends on.

"There’s no excuse for cheating when the fundamental code for cadets is that they should not lie, cheat or steal," Bakken said. "Therefore when the military tries to downplay effects of cheating at the academy, we're really downplaying the effects on the military as a whole. We rely on the military to tell us honestly when we should fight wars, and when we can win them."

Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy said West Point's disciplinary system is effective.

“The Honor process is working as expected and cadets will be held accountable for breaking the code," McCarthy said in a statement.

“The honor system at West Point is strong and working as designed," Lt. Gen. Darryl Williams, the academy's superintendent, said in a statement. "We made a deliberate decision to uphold our academic standards during the pandemic. We are holding cadets to those standards.”

Army Col. Mark Weathers, West Point's chief of staff, said in an interview Monday that he was "disappointed" in the cadets for cheating, but he did not consider the incident a serious breach of the code. It would not have occurred if the cadets had taken the exam on campus, he said.

Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., who leads the personnel panel of the House Armed Services Committee, said she found the scandal deeply troubling and West Point must provide more transparency to determine the scope of cheating.

"Our West Point cadets are the cream of the crop and are expected to demonstrate unimpeachable character and integrity," Speier said. "They must be held to the same high standard during remote learning as in-person."

Instructors initially determined that 72 plebes, or first-year cadets, and one yearling, or second-year cadet, had cheated on a calculus final exam in May. Those cadets all made the same error on a portion of the exam.

Recently concluded investigations and preliminary hearings for the cadets resulted in two cases being dismissed for lack of evidence and four dropped because the cadets resigned. Of the remaining 67 cases, 55 cadets were found in violation of the honor code and enrolled in a program for rehabilitation Dec. 9. Three more cadets admitted cheating but were not eligible to enroll in what is called the Willful Admission Program.

Cadets in the program are matched with a mentor and write journals and essays on their experience. The process can take up to six months. Cadets in the program are essentially on academic probation.

The remaining cadets accused of cheating face administrative hearings in which a board of cadets will hear the case and decide whether a violation of the code occurred. Another board will recommend penalties, which could include expulsion. West Point's superintendent has the final say on punishment.

How it's different from the 1976 scandal

One of the biggest cheating scandals among the nation's taxpayer-funded military colleges occurred in 1976 when 153 cadets at West Point resigned or were expelled for cheating on an electrical engineering exam.

The current cheating incident is considerably less serious, said Jeffery Peterson, senior advisor, Character Integration Advisory Group which reports to the superintendent and a retired colonel.

"They're early in their developmental process," Peterson said. "And so on occasion, these incidents happen, but we have a system in place to deal with them when they do."

Less than half as many cadets were involved in the current cheating case, and all but one was a first-year student, Peterson said. The first-year students are relatively new to the expectations and programs designed to develop ethics and leadership at the academy. In 1976, the scandal involved third-year cadets. Of those caught cheating, 98 returned to West Point and graduated with the class of 1978, Peterson said.

Other military academies have been tainted by academic scandals: In 1992, 125 midshipmen at the Naval Academy were caught in a cheating scandal, and 19 cadets at the Air Force Academy were suspended for cheating on a test.

In 2020, the pandemic has overturned college life as distance learning and exams supplanted in-person learning. West Point isn't alone in discovering misconduct among students. The University of Missouri caught 150 students cheating in the spring and fall semesters, the Kansas City Star reported.

West Point switched to remote learning after spring break last year as the pandemic spread.

The honor code remains strong at West Point despite the pandemic, Weathers said.

"Cadets are being held accountable for breaking the code," he said. "While disappointing, the Honor System is working, and these 67 remaining cases will be held accountable for their actions."

USA TODAY

(Reuters) - Chinese vaccine maker Sinovac Biotech Ltd's COVID-19 vaccine has shown to be effective in late-stage trials in Brazil, the Wall Street Journal reported on Monday, citing people involved in the vaccine's development.

Sao Paulo state's Butantan Institute, which is organizing the late-stage trials of Sinovac's vaccine CoronaVac in Brazil, said on Monday that any reports on the efficacy of the shot before a Wednesday announcement were "mere speculation."

Brazil is the first country to complete late-stage trials of CoronaVac, which is also being tested in Indonesia and Turkey, the Journal reported https://www.wsj.com/articles/sinovacs-covid-19-vaccine-shown-to-be-effective-in-brazil-trials-11608581330?mod=latest_headlines.

The results from the Brazil trials put CoronaVac above the 50% threshold that international scientists deem necessary to protect people, the Journal report said.

Butantan is poised on Wednesday to announce CoronaVac's efficacy rate, according to the Journal.

Sinovac did not immediately respond to Reuters' request for comment.

Sinovac and AstraZeneca Plc's vaccine candidates may be ready for use in Brazil by mid-February, the country's health minister said last week.

London (ANI): Liverpool's Andrew Robertson said his team capitalised on all the chances that they got during their 7-0 win over Crystal Palace, adding that it was "as close to a perfect as we can get away from home."

"Yeah, obviously when you go early kick-off on Saturday and you go first, it only works to your advantage if you pick up the points. Luckily we have done that today in a very good fashion," the club's official website quoted Robertson as saying.

"We have taken all the chances that were presented to us - seven goals and a clean sheet and the important thing is the three points. Now we can sit back and enjoy the weekend of football knowing that we have got our three points in the bag and let's see what unfolds. But it was as close to perfect as we can get away from home," he added.

Liverpool were on their best during the Premier League clash on Saturday. Takumi Minamino handed the team a one-goal lead inside three minutes. Sublime strikes from Sadio Mane and Roberto Firmino followed before the interval. Although Crystal Palace created a handful of opportunities, they failed to capitalise on them.

Liverpool showed no let-up after the break as Jordan Henderson netted the fourth goal before Firmino clinically added goal number five.

Mohamed Salah came off the bench to round off the scoring with a close-range header followed by a magnificent curling effort to make it seven. With this victory, Liverpool consolidated their top position on the table as they now have 31 points, five points ahead of the second-placed club Everton.

Robertson also expressed delight over his side being able to keep a clean sheet in the match.

"Yeah, the seven goals will obviously be concentrated on but me, Ali, Trent, Fab, Joel, Hendo, everyone, we are all buzzing because coming away from home - especially Crystal Palace, a really tough place to come - and getting a clean sheet is great," he said. (ANI)

NEW YORK (Reuters) - New York City is overhauling how it admits students to some of its most competitive public schools to make them less segregated by race and wealth, Mayor Bill de Blasio said on Friday.

Some selective Manhattan high schools, particularly in wealthy neighborhoods, are allowed to give children who live nearby priority in admissions, which has tended to put children living in poorer neighborhoods at a disadvantage. These so-called geographic priorities will be ended over the coming two years, making it easier for children from anywhere to apply for a spot, the mayor said at a news conference.

The city will also end "screening" practices at hundreds of middle schools that admit students based on a mixture of grades, test results, attendance rates.

These practices led to disproportionately high admissions of white and Asian students and fewer Black and Latino students in the best-performing schools in the nation's largest and most diverse education system, which serves some 1.1 million children. Admissions will instead be determined by a random lottery.

"We have been doing this work for seven years to more equitably redistribute resources throughout our school system," de Blasio told reporters. "I think these changes will improve justice and fairness."

Although calls to overhaul school admissions long predate the novel coronavirus pandemic, the disruption caused by school closures to stem the spread of COVID-19 was a factor in the overhaul: for example, some state exams were canceled and attendance rates became more difficult to track, Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza told reporters.

The New York Civil Liberties Union welcomed the changes but said they should have come sooner, and called for the permanent removal of screening at the high-school level.

"It should not have taken a pandemic to finally remove discriminatory admissions screens for children applying to middle school and to remove the egregious district priorities that concentrate wealth and resources into a few schools," NYCLU organizer Toni Smith-Thompson said in a statement.

States and cities across the country are moving to put teachers near the front of the line to receive a coronavirus vaccine, in an effort to make it safer to return to classrooms and provide relief to struggling students and weary parents.

In Arizona, where many schools have moved online in recent weeks amid a virus surge, Gov. Doug Ducey declared that teachers would be among the first people inoculated. “Teachers are essential to our state,” he said. Utah’s governor talked about possibly getting shots to educators this month. And Los Angeles officials urged prioritizing teachers alongside firefighters and prison guards.

But in districts where children have spent much of the fall staring at laptop screens, including some of the nation’s largest, it may be too early for parents to get their hopes up that public schools will throw open their doors soon, or that students will be back in classrooms full time before next fall.

Given the limited number of vaccines available to states and the logistical hurdles to distribution, including the fact that two doses are needed several weeks apart, experts said that vaccinating the nation’s three million schoolteachers could be a slow process, taking well into the spring.

And even once enough educators are inoculated for school officials and teachers’ unions — which hold considerable power in many large districts — to consider it safe to reopen classrooms, schools will likely need to continue requiring masks and distancing students for many months, experts said, until community spread has sharply dropped, possibly by summer.

“I think some people have in their head that we’re going to start rolling out the vaccine and all this other stuff is going to go away,” said Marcus Plescia, the chief medical officer at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, which represents public health agencies.

But in schools, as in daily life, he said, there will be no quick fix. “My feeling is that we’re all going to be wearing masks and keeping our distance and trying to be careful around each other for probably most of 2021.”

Vaccination could have the largest impact on schools in places where teaching has remained entirely remote this fall, or where students have spent limited time in the classroom. That includes many big cities and districts in the Northeast and on the West Coast, which have been the most cautious about reopening despite little evidence of schools — and elementary schools in particular — stoking community transmission.

At the same time, there are many schools in the South, the Midwest and the Mountain States where a large percentage of teachers and students are already in classrooms, and where a vaccine would most likely not have as much impact on policy. But even in some of those parts of the country, such as Arizona, distance learning has resumed in recent weeks as coronavirus cases have surged, and vaccinating teachers could help reduce such disruptions.

The nation’s roughly three million full-time teachers are considered essential workers by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which means that in states that follow federal recommendations, they would be eligible to receive the vaccine after hospital employees and nursing home residents.

But the essential worker group is huge — some 87 million Americans — and states will have flexibility in how they prioritize within that population. Many more people work in schools than just teachers, including nurses, janitors and cafeteria workers, and it is unclear how many of them would be included on the high-priority list.

Public health experts disagree on where teachers should fall, with some saying that in-person education is crucial and others noting that teachers generally have better protections and pay than many other essential workers, such as those in meatpacking plants and day cares. Many teachers have not been in their classrooms since March, either because their districts have not physically reopened, or because they have a medical waiver exempting them.

Groups that represent teachers, for the most part, are eager to see their members fast-tracked for vaccines. Last month, more than 10 educational organizations, including the nation’s two largest teachers’ unions, wrote to the CDC asking that school employees be considered a priority group.

“Our students need to come back to school safely,” they wrote. “Educators want to welcome them back, and no one should have to risk their health to make this a reality.”

Teachers in districts that have already opened classrooms, like Houston and Miami, should be prioritized for shots, said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, which includes some of the country’s largest local chapters.

“Let’s have an alignment here of the schools that are reopening for in-person learning and availability of vaccine,” she said. As more teachers are vaccinated, she added, “we believe that more and more schools can open in person.”

In New York City, home to by far the country’s largest school system, Mayor Bill de Blasio has confidently predicted that many more of the city’s 1.1 million students will be able to return to classrooms this spring as the vaccine is distributed to educators.

Michael Mulgrew, who runs the United Federation of Teachers, the local union, said he thought that timeline might be overconfident — “I don’t think it’s around the corner,” he said of full reopening — but agreed that the thousands of teachers in New York City who were working in person should be among the first educators to get their shots.

Other union leaders, however, were wary about efforts to prioritize within their ranks.

“We don’t want to be in the business of putting a hierarchy in place,” said Becky Pringle, who runs the country’s largest teachers’ union, the National Education Association, “because some of our members are being bullied into returning back to classrooms. That’s not safe, we don’t want to support that.”

Teacher health concerns and union political power have played a significant role in states and cities that have not yet opened their schools, including Los Angeles and Chicago, the nation’s largest districts after New York. In California, where teachers’ unions hold great sway, state and local health rules will not allow the Los Angeles Unified School District to reopen classrooms until the rates of known cases drop significantly, regardless of the vaccine.

Austin Beutner, the superintendent, said he would like to use the district’s extensive testing infrastructure to systematically vaccinate teachers, school nurses and others. But he does not expect a return to pre-pandemic conditions — dozens of children in classrooms five days a week, without social distancing or masks — until the end of 2021.

“If we were able to provide those who work in a school with a vaccine tomorrow, great. They themselves are protected. But they could also be a silent spreader,” he said, referring to the fact that it has not yet been determined if vaccinated people can still carry and spread the coronavirus. And students are unlikely to receive shots before the fall because pediatric trials have only recently begun.

In Chicago, the teachers’ union is fighting a plan to begin returning some students to schools early next year. “Obviously, if school is continuing remote, there’s less urgency around the vaccination,” said the Chicago Teachers Union’s president, Jesse Sharkey.

Asked if he could imagine schools opening before fall 2021, Sharkey said yes, but he suggested it would have more to do with controlling the spread of the virus than vaccinating teachers. “With mitigation strategies in place, and with a reasonably low level of community spread, I do think that we could get to open schools,” he said.

Not every union leader expects all of their members to eagerly line up for inoculation. “Some don’t want to go back unless there is a vaccine, and others absolutely don’t believe in it,” said Marie Neisess, president of the Clark County Education Association, which represents more than 18,000 educators in Nevada.

In California, E. Toby Boyd, president of the state’s largest teachers’ union, said educators have been told they will be in the second wave of vaccinations. But some teachers may be reluctant to be among the first recipients.

“My members are anxious to get back to the classroom, but they’re skeptical,” said Boyd, whose organization, the California Teachers Association, represents some 300,000 members. “We need to be sure it’s safe and there are no lasting side effects.”

Teachers in California also continue to push for other safety measures that they think need to be addressed before normal school can resume. “We view the vaccine as one important layer in preventing school outbreaks,” said Bethany Meyer, a special-education teacher and union leader in Oakland, California.

“We also need testing and tracing and other mitigation measures, and that’s going to be the case for some time,” Meyer said, adding, “A vaccine is important, but our thinking is longer term than that.”

In places like Miami, where public schools have been open for much of the fall, vaccinations could have a different effect. Karla Hernandez-Mats, the leader of United Teachers of Dade, said she believed that widespread vaccination among educators there would help reduce the chaos caused by frequent quarantines and classroom closures.

The vaccine, she said, “would create more of a sense of normalcy, and it would bring a lot of relief to a lot of teachers working in person right now.”

The New York Times.

Turkey's state-run aid agency built classrooms and offices for a primary school in eastern Uganda.

Turkey's Ambassador to Uganda Fikret Kerem Alp and Uganda's Parliament Speaker Rebecca Kadaga inaugurated the facility on Tuesday.

The development is in line with Turkey’s agenda of improving the quality of education and the learning environment for African children.

Yahya Acu, country coordinator for the Turkish International Cooperation and Development Agency (TIKA), said their intention is to help children access education in a conducive and secure environment.

“This is one of the investments from the Turkish people and will chiefly benefit students and the school community in learning, teaching and their social lives,” he said.

Kadaga thanked the Turkish people for helping the government achieve their target of improving the quality of education./aa

Matt Richtel

Alice McGraw, 2 years old, was walking with her parents in Lake Tahoe this summer when another family appeared, heading in their direction. The little girl stopped.

“Uh-oh,” she said and pointed: “People.”

She has learned, her mother said, to keep the proper social distance to avoid risk of infection from the coronavirus. In this and other ways, she’s part of a generation living in a particular new type of bubble — one without other children. They are the toddlers of COVID-19.

Gone for her and many peers are the play dates, music classes, birthday parties, the serendipity of the sandbox or the side-by-side flyby on adjacent swingsets. Many families skipped day care enrollment in the fall, and others have withdrawn amid the new surge in coronavirus cases.

With months of winter isolation looming, parents are growing increasingly worried about the developmental effects of the ongoing social deprivation on their very young children.

“People are trying to weight pros and cons of what’s worse: putting your child at risk for COVID or at risk for severe social hindrance,” said Suzanne Gendelman, whose daughter, Mila, 14 months old, regularly spent rug time with Alice McGraw before the pandemic.

“My daughter has seen more giraffes at the zoo more than she’s seen other kids,” Gendelman said.

It is too early for published research about the effects of the pandemic lockdowns on very young children, but childhood development specialists say that most children will likely be OK because their most important relationships at this age are with parents.

Still, a growing number of studies highlight the value of social interaction to brain development. Research shows that neural networks influencing language development and broader cognitive ability get built through verbal and physical give-and-take — from the sharing of a ball to exchanges of sounds and simple phrases.

These interactions build “structure and connectivity in the brain,” said Kathryn Hirsh-Pasek, director of the Infant Language Laboratory at Temple University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “They seem to be brain feed.”

In infants and toddlers, these essential interactions are known as “serve-and-return,” and rely on seamless exchanges of guttural sounds or simple words.

Hirsh-Pasek and others say that technology presents both opportunity and risk during the pandemic. On one hand, it allows children to engage in virtual play by Zoom or FaceTime with grandparents, family friends or other children. But it can also distract parents who are constantly checking their phones to the point that the device interrupts the immediacy and effectiveness of conversational duet — a concept known as “technoference.”

John Hagen, professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Michigan, said he would be more concerned about the effect of lockdowns on young children, “if this were to go on years and not months.”

“I just think we’re not dealing with any kinds of things causing permanent or long-term difficulties,” he said.

Hirsh-Pasek characterized the current environment as a kind of “social hurricane” with two major risks: Infants and toddlers don’t get to interact with one another and, at the same time, they pick up signals from their parents that other people might be a danger.

“We’re not meant to be stopped from seeing the other kids who are walking down the street,” she said.

Just that kind of thing happened to Casher O’Connor, 14 months, whose family recently moved to Portland, Oregon, from San Francisco. Several months before the move, the toddler was on a walk with his mother when he saw a little boy nearby.

“Casher walked up to the 2-year-old, and the mom stiff-armed Cash not to get any closer,” said Elliott O’Connor, Casher’s mother.

“I understand,” she added, “but it was still heartbreaking.”

Portland has proved a little less prohibitive place for childhood interaction in part because there is more space than in the dense neighborhoods of San Francisco, and so children can be in the same vicinity without the parents feeling they are at risk of infecting one another.

“It’s amazing to have him stare at another kid,” O’Connor said.

“Seeing your kid playing on a playground with themselves is just sad,” she added. “What is this going to be doing to our kids?”

The rise of small neighborhood pods or of two or three families joining together in shared bubbles has helped to offset some parents’ worries. But new tough rules in some states, like California, have disrupted those efforts because playgrounds have been closed in the latest COVID-19 surge and households have been warned against socializing outside their own families.

Plus, the pods only worked when everyone agreed to obey the same rules, and so some families simply chose to go it alone.

That’s the case of Erinn and Craig Sheppard, parents of a 15-month-old, Rhys, who live in Santa Monica, California. They are particularly careful because they live near the little boy’s grandmother, who is in her 80s. Sheppard said Rhys has played with “zero” children since the pandemic started.

“We get to the park, we Clorox the swing and he gets in and he has a great time and loves being outside and he points at other kids and other parents like a toddler would,” she said. But they don’t engage.

One night, Rhys was being carried to bed when he started waving. Sheppard realized that he was looking at the wall calendar, which has babies on it. It happens regularly now. “He waves to the babies on the wall calendar,” Sheppard said.

Experts in child development said it would be useful to start researching this generation of children to learn more about the effects of relative isolation. There is a distant precedent: Research was published in 1974 that tracked children who lived through a different world-shaking moment, the Great Depression. The study offers reason for hope.

“To an unexpected degree, the study of the children of the Great Depression followed a trajectory of resilience into the middle years of life,” wrote Glen Elder, author of that research.

Brenda Volling, a psychology professor at the University of Michigan and an expert in social and emotional development, said one takeaway is that Depression-era children who fared best came from families who overcame the economic fallout more readily and who, as a result, were less hostile, angry and depressed.

To that end, what infants, toddlers and other children growing up in the COVID era need most now is stable, nurturing and loving interaction with their parents, Volling said.

“These children are not lacking in social interaction,” she said, noting that they are getting “the most important” interaction from their parents.

A complication may involve how the isolation felt by parents causes them to be less connected to their children.

“They are trying to manage work and family in the same environment,” Volling said. The problems cascade, she added, when parents grow “hostile or depressed and can’t respond to their kids, and get irritable and snap.”

“That’s always worse than missing a play date.”

The New York Times.

More...

Tanzania’s hospitality paradise, the Ngurdoto Mountain Lodge, which used to draw many international visitors to the country’s northern tourist circuit, has been converted into a students’ dormitory on a lease agreement as the gloomy business climate drove the property to the brink of financial ruin.

The novel coronavirus outbreak was the final straw for the battered hotel industry, which suffered losses due to travel restrictions to curb the disease.

As the virus spread, the country’s hospitality industry suffered as corporate and business travelers, who account for the bulk of hotel revenues, cut back on travel spending.

The Ngurdoto Mountain Lodge, renowned for hosting the 2008 Leon H. Sullivan Summit, was forced to shut down due to poor business as a result of the outbreak.

Eliamani Sedoyeka, the principal of the Arusha Institute of Accountancy, confirmed that the college has leased the hotel.

According to Sedoyeka, the move to lease the hotel was prompted by a surge of new students who have been admitted this year.

“We were overwhelmed by new requests for admission. That’s why we decided to find a new accommodation,” he said.

The landmark company that manages the hotel confirmed the agreement, adding that each student would pay 400,000 Tanzanian shillings (around US$173) per year.

According to Sedoyeka, some rooms have been facelifted to include double beds.

Equipped with 300 bedrooms and seven presidential suites, the hotel, built in 2003, is reminiscent of former Democratic Republic of Congo President Mobutu Sese Seko’s Gbadolite Presidential Palace deep in the Congo jungle.

“Initially, some students were not willing to move in. But now, everyone is motivated to settle there. Some of them really like the environment. They share videos on social media,” he said./aa

PHOENIX — An estimated 50,000 students vanished from Arizona's public district and charter schools over the summer, preliminary student count numbers for the 2020-2021 school year show.

That means the state has lost 5% of its students between this school year and the end of last. Numbers also show kindergarten enrollment is down by 14%.

Because the figures are early, it's unclear where students have gone. The state's population has not shifted enough for enrollment to plummet so dramatically. The number of families filing for homeschool has increased, but not by 50,000.

Education advocates fear some school-age students are not in school at all, and that the lag in kindergarten enrollment means that children in Arizona are losing out on early lessons vital to a child's learning experience.

"It's a lost year, and that's really tragic when you think about it," said Siman Qaasim, president of the Children's Action Alliance, an Arizona nonprofit.

The dramatic enrollment drops could also come with devastating and long-lasting financial repercussions for school districts. A loss of students will result in a loss of funding, which is tied to number of students. Districts and charters with more students receive more funding, because funding is calculated per student.

The state will provide grants through federal aid money to help schools make up for lost revenue, but districts don't yet know how much they'll receive or if the money will make up for the funding gaps caused by plunging enrollment.

Big districts report big enrollment drops

District schools have been losing enrollment for a decade, which is in part because of the proliferation of charter schools in the state. However, the state's estimated enrollment drop for this year, 5%, includes charter schools because they are public schools that receive state funding.

Part of the enrollment drop is because of an increase in homeschooled students. For example, in Maricopa County, 3,774 families have reported since August that they planned to homeschool this year, compared with 971 during the same period in 2019, according to information from the Maricopa County School Superintendent office.

Dennis Goodwin is the superintendent of the Murphy Elementary School District in Phoenix. About 1,500 students attend Murphy schools, and most are low-income. Enrollment at his district is down by about 8%, he said.

Some families really wanted to send their children in-person and have switched to charters, he said. In other cases, students might not be schooling at all, he said, particularly in families where parents have to work and older kids are taking care of their siblings.

"They may have thought about signing up and doing online, but I think right now they're just waiting for school to start up again," he said.

But in Murphy, COVID-19 is not under control enough to reopen school, he said.

Struggles to keep students engaged

Murphy is searching for the students it has lost.

District officials have worked to follow up with students who didn't come back this school year to see if they've enrolled somewhere else. But the district's population tends to move a lot and is difficult to track, Goodwin said.

"There's a lot of legwork that has to go to get it to find the kids and get them to make sure that they're staying in contact," he said.

Sometimes, officials have to knock on doors. In one case, the district discovered that a sixth- and second-grader stopped logging on because their parents were in the hospital and the family's internet was shut off. Murphy loaned the students wireless internet hotspots.

In Arizona, school is compulsory, which means state law requires every child between the ages of 6 and 16 to attend school.

But that law is difficult to enforce in a vast educational landscape.

Arizona is an open enrollment state, so students don't have to attend their neighborhood schools, and districts don't track every child in their boundaries.

Some of the sharpest enrollment declines are at the kindergarten level, which is not mandatory in Arizona. But students learn a lot in kindergarten, including early lessons in reading and math.

Qaasim said she is particularly concerned for students living in poverty, who tend to fall behind faster than students from wealthier backgrounds. Putting off school for a year may also mean developmental disabilities in students can go undetected for longer, meaning less academic intervention.

"We're just so worried that so many will be unprepared," she said.

Enrollment declines cost money

Arizona's Tucson Unified school district has seen a 4.9% drop in enrollment. A task force was formed to try to reverse the enrollment loss, Superintendent Gabriel Trujillo said at a recentschool board meeting.

"Every student leaving the district is not just a number," he said. "We have to be very, very strategic, we have to be very, very swift in our attempt to re-engage those families."

The district estimates it will lose about $25 million this year because of the enrollment declines and other factors.

Gov. Doug Ducey has promised school federal funding in the form of an enrollment stability grant, which he said would guarantee funding up to 98% of a school's enrollment in the previous school year. The grant process is ongoing, so schools will not know the final amount until late November.

Estimates so far are not adding up to the 98% guarantee.

Tucson estimates a grant of $20.5 million, about $5 million short of the funding lost this school year.

And the grants are only available this year, with no promise for extra funding in 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on student academics, however, will likely persist for years. Qaasim said schools are facing a funding cliff, all while students need as much intervention as possible.

"That costs money," she said.

Every weekday morning, Paul Yenne sets up five different devices — including two laptops, an iPhone and a screen-caster that projects videos to a large screen — to get ready for the 19 fifth-grade students who come to his classroom and the six who log on from home.

The Colorado school district where Yenne works offers in-person and online classes simultaneously, with one teacher responsible for both as the Covid-19 pandemic touches every facet of education.

Yenne, 31, delivers the day’s lesson, his eyes continuously darting between the students in front of him and those stacked on a virtual grid on a laptop at the front of the room.

Despite his desire to create a seamless classroom experience for both groups, one inevitably gets left out, he said. If the technology breaks down, his classroom students have to wait until he fixes it, and if there's an in-person issue, it's the other way around, he said.

“The most exhausting thing is just to try and hold attention in two different places and give them at least somewhat equal weight,” he said. “What kind of wears on me the most is just thinking, 'I don't know that I did the best for every kid,' which is what I try and do every day when I go in."

While most K-12 schools have chosen to go either online or in person at one time, the double duty model is among the most labor-intensive, according to education experts. Yet it's increasingly becoming the new norm around the country, and with less than a quarter of the school year down, many teachers say they're already exhausted.

They have received little training and resources are scarce, they say, but they worry that speaking up could cost them their jobs.

”I think that kind of exhaustion we had from last year has kind of compounded as now we're being asked to do essentially two jobs at once,” Yenne said. “The big question right now is, 'How long can we continue doing this?'"

Afraid to speak out

While many schools call this form of teaching “hybrid,” experts label it “concurrent teaching” or “hyflex," modes originally designed for university and graduate-level students.

Brian Beatty, an associate professor at San Francisco State University who pioneered the hyflex program, said it was designed to have more than a single mode of interaction going on in the same class and typically involves classroom and online modes that can be synchronous or asynchronous.

The aim was to provide students not in the classroom with as good an educational experience as those who were, and it was intended for students who chose to be taught that way on a regular or frequent basis, he said. The model was created for adults at the undergraduate and graduate level who made the choice and were able to manage themselves.

“The context of the situation at the elementary level is so different than the situation that we designed this for," he said. "A lot of the principles can work but challenges are also a lot more extreme, especially around managing students.”

Image: New York City School Children Return To In-Person Classes (Michael Loccisano / Getty Images)

Sophia Smith, a literary enrichment teacher for kindergarten through third-grade students in Des Plaines, Illinois, said her elementary school allowed little time for training and planning before teachers were thrust into the dual mode.

She said 40 percent of her students are online, and she spends much of her time going back and forth between online and classroom students, leaving little time for meaningful instruction.

"It's extremely chaotic," she said, adding that if school officials were to visit her classroom, they would understand how their decisions about hybrid education really affected teachers.

Smith worries the model will become an accepted norm, mostly because teachers who are struggling to keep up are scared to speak out.

“We're afraid to lose our jobs," she said. "We're afraid that the district will come back and treat us differently or say things differently, like, 'Nobody else is complaining, so why is it you?'"

Smith said she is speaking up now because she wants other teachers to feel more comfortable doing so.

Matthew Rhoads, an education researcher and author of "Navigating the Toggled Term: Preparing Secondary Educators for Navigating Fall 2020 and Beyond," said schools added a livestream component to their curriculum in a panicked effort to offer an online choice to families. But much of the implementation was not thought out, he said, leaving teachers to deal with the fallout.

Teachers are beyond exhausted, said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, one of the largest teachers unions in the country.

“This is the worst of all worlds,” she said. “The choice to do that came down to money and convenience, because it certainly wasn’t about efficacy and instruction.”

Long-term consequences

David Finkle, a ninth-grade teacher at a Florida high school, said he has not been able to sleep despite being depleted of energy after a full day of online and in-person instruction. The veteran teacher of nearly 30 years stopped running, writing creatively and doing any of the other activities he enjoys when school began in August.

“It's been very hard for me to focus on my other creative stuff outside of school because school is wiping me out," he said, adding that it's difficult to keep up with grading because it takes so long to plan lessons for the two groups.

"I wish I could focus on one set of students," he said.

Teachers are reporting high levels of stress and burnout around the country, including in Kansas, Michigan and Arkansas. In Utah, the Salt Lake Tribune reported, principals say their teachers are having panic attacks while juggling both.

High levels of teacher stress affect not only students and their quality of education, but the entire profession, said Christopher McCarthy, chair of the educational psychology department at the University of Texas at Austin.

"When teachers are under a lot of stress, they are also a lot more likely to leave the profession, which is a very bad outcome," he said.

Already, 28 percent of educators said the Covid-19 pandemic has made them more likely to retire early or leave the profession, according to a nationwide poll of educators published in Augustby the National Education Association, the country's largest teachers union.

Rhoads, the education researcher, said retaining high-caliber teachers is crucial, especially now, but if the hyflex model continues without adequate support, a mass teacher shortage is inevitable.

Such an event would have far-reaching effects, accelerating school district consolidations and causing some states to lower their standards and licensing requirements for teachers, he said.

For instance, the Missouri Board of Education passed an emergency rule in anticipation of a pandemic-related teacher shortage that made it easier to become a substitute. Instead of 60 hours of college credit, eligible substitutes need only a high school diploma, to complete a 20-hour online training course and pass a background check, according to the Associated Press.

Iowa relaxed relaxed coursework requirements and lowered the minimum age for newly hired substitutes from 21 to 20, the AP reported, and in Connecticut, college students have been asked to step in as substitutes.

Supporting teachers

Paige, a middle school teacher in central Florida who did not want her full name used to protect her job, said teachers at her school received less than a week’s notice that they would be teaching in the classroom and online concurrently. They received no training on platforms or logistics, she said.

Since the beginning of the year, she has struggled with internet accessibility and technical glitches.

“We need greater bandwidth," she said. "I have five kids turn on the camera and suddenly nothing is working in real time anymore. We need more devices."

She said teachers doing double duty should receive improved products, technology training and professional guidance and mentorship. Other teachers said having a day or even half a day for planning would help.

McCarthy, the educational psychologist, said the best support teachers can get when demands are high are the resources to deal with the challenges.

"What's happening right now is lack of resources mixed with a lot of uncertainty," he said, "and that is a toxic blend."

BEIJING (AP) — Following scathing political attacks from the Trump administration, China on Friday defended its Confucius Institutes as apolitical facilitators of cultural and language exchange.

The administration last week urged U.S. schools and colleges to rethink their ties to the institutes that bring Chinese language classes to America but, according to federal officials, also invite a “malign influence” from China.

Foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian disputed that characterization and accused Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and U.S. politicians of acting out of “ideological prejudice and personal political interests” and having “deliberately undermined the cultural and educational exchanges and cooperation between China and the U.S.”

The U.S. politicians should “abandon the Cold War mentality and zero-sum thinking ... and stop politicizing related programs of educational exchange, obstructing normal cultural exchanges between the two sides, and damaging mutual trust and cooperation between China and the U.S.," Zhao said at a daily briefing.

Patterned after the British Council and Alliance Francaise, the Confucius Institutes are unique in that they set up operations directly on U.S. campuses and schools, drawing mounting scrutiny from U.S. officials amid increased tensions with China.

In letters to universities and state education officials, the State Department and Education Department said the program gives China's ruling Communist Party a foothold on U.S. soil and threatens free speech. Schools are being advised to examine the program’s activities and “take action to safeguard your educational environments.”

More than 60 U.S. universities host Confucius Institutes through partnerships with an affiliate of China’s Ministry of Education, though the number has lately been dropping. China provides teachers and textbooks and typically splits the cost with the university. The program also brings Chinese language classes to about 500 elementary and secondary classrooms.

In last week's letters, U.S. officials drew attention to China’s new national security law in Hong Kong, which critics say curtails free expression and other liberties. The letters cite recent reports that some U.S. college professors are allowing students to opt out of discussions on Chinese politics amid fears that students from Hong Kong or China could be prosecuted at home.

Such fears are “well justified,” officials said, adding that at least one student from China was recently jailed by Chinese authorities over tweets he posted while studying at a U.S. university.

At least 39 universities have announced plans to shutter Confucius Institute programs since the start of 2019, according to a log published by the National Association of Scholars, a conservative nonprofit group.

Other nations have also sought to curb China’s influence in their schools, with regional educational departments in Canada and Australia cutting ties with the institutes.